[ad_1]

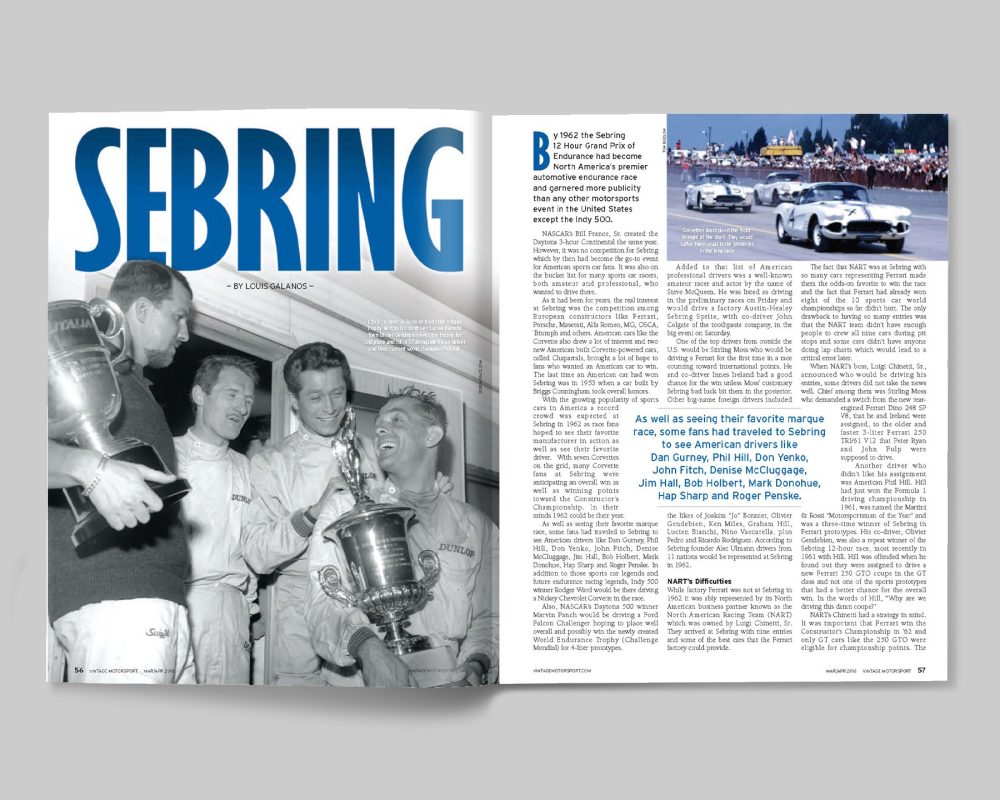

The 72nd Twelve Hours of Sebring is just days away and top of mind this week is always the dynamic history associated with this storied endurance race in Central Florida. By 1962 the Sebring 12 Hour Grand Prix of Endurance had become North America’s premier endurance race and author Louis Galanos expertly details the dramatic race in VM’s March/April 2018 issue. Aptly titled “Sebring” – enjoy this journey into the Vintage Motorsport archives.

Buy This Issue | Access the Digital Issue | Subscribe to Vintage Motorsport

NASCAR’s Bill France, Sr. created the Daytona 3-hour Continental the same year. However, it was no competition for Sebring which by then had become the go-to event for American sports car fans. It was also on the bucket list for many sports car racers, both amateur and professional, who wanted to drive there.

As it had been for years, the real interest at Sebring was the competition among European constructors like Ferrari, Porsche, Maserati, Alfa Romeo, MG, OSCA, Triumph and others. American cars like the Corvette also drew a lot of interest and two new American built Corvette-powered cars, called Chaparrals, brought a lot of hope to fans who wanted an American car to win. The last time an American car had won Sebring was in 1953 when a car built by Briggs Cunningham took overall honors.

With the growing popularity of sports cars in America a record crowd was expected at Sebring in 1962 as race fans hoped to see their favorite manufacturer in action as well as see their favorite driver. With seven Corvettes on the grid, many Corvette fans at Sebring were anticipating an overall win as well as winning points toward the Constructor’s Championship. In their minds 1962 could be their year.

As well as seeing their favorite marque race, some fans had traveled to Sebring to see American drivers like Dan Gurney, Phil Hill, Don Yenko, John Fitch, Denise McCluggage, Jim Hall, Bob Holbert, Mark Donohue, Hap Sharp and Roger Penske. In addition to those sports car legends and future endurance racing legends, Indy 500 winner Rodger Ward would be there driving a Nickey Chevrolet Corvette in the race.

Also, NASCAR’s Daytona 500 winner Marvin Panch would be driving a Ford Falcon Challenger hoping to place well overall and possibly win the newly created World Endurance Trophy (Challenge Mondial) for 4-liter prototypes.

Added to that list of American professional drivers was a well-known amateur racer and actor by the name of Steve McQueen. He was listed as driving in the preliminary races on Friday and would drive a factory Austin-Healey Sebring Sprite, with co-driver John Colgate of the toothpaste company, in the big event on Saturday.

One of the top drivers from outside the U.S. would be Stirling Moss who would be driving a Ferrari for the first time in a race counting toward international points. He and co-driver Innes Ireland had a good chance for the win unless Moss’ customary Sebring bad luck bit them in the posterior. Other big-name foreign drivers included the likes of Joakim “Jo” Bonnier, Olivier Gendebien, Ken Miles, Graham Hill, Lucien Bianchi, Nino Vaccarella, plus Pedro and Ricardo Rodríguez. According to Sebring founder Alec Ulmann drivers from 11 nations would be represented at Sebring in 1962.

NART’s DifficultiesWhile factory Ferrari was not at Sebring in 1962 it was ably represented by its North American business partner known as the North American Racing Team (NART) which was owned by Luigi Chinetti, Sr. They arrived at Sebring with nine entries and some of the best cars that the Ferrari factory could provide.

Buy This Issue | Access the Digital Issue | Subscribe to Vintage Motorsport

The fact that NART was at Sebring with so many cars representing Ferrari made them the odds-on favorite to win the race and the fact that Ferrari had already won eight of the 10 sports car world championships so far didn’t hurt. The only drawback to having so many entries was that the NART team didn’t have enough people to crew all nine cars during pit stops and some cars didn’t have anyone doing lap charts which would lead to a critical error later.

When NART’s boss, Luigi Chinetti, Sr., announced who would be driving his entries, some drivers did not take the news well. Chief among them was Stirling Moss who demanded a switch from the new rearengined Ferrari Dino 248 SP V8, that he and Ireland were assigned, to the older and faster 3-liter Ferrari 250 TRI/61 V12 that Peter Ryan and John Fulp were supposed to drive.

Another driver who didn’t like his assignment was American Phil Hill. Hill had just won the Formula 1 driving championship in 1961, was named the Martini & Rossi “Motorsportsman of the Year” and was a three-time winner of Sebring in Ferrari prototypes. His co-driver, Olivier Gendebien, was also a repeat winner of the Sebring 12-hour race, most recently in 1961 with Hill. Hill was offended when he found out they were assigned to drive a new Ferrari 250 GTO coupe in the GT class and not one of the sports prototypes that had a better chance for the overall win. In the words of Hill, “Why are we driving this damn coupe?”

NART’s Chinetti had a strategy in mind. It was important that Ferrari win the Constructor’s Championship in ’62 and only GT cars like the 250 GTO were eligible for championship points. The sports prototypes were not. Chinetti knew that with their vast Sebring experience Hill and Gendebien had a better than even chance to win their class and the allimportant nine points toward the championship.

Given their druthers, Hill and Gendebien would have preferred to drive the Ferrari 250 TRI/61 that carried both to victory at Sebring in 1961. This same car also won the 24 Hours of Le Mans the same year before it was sold to the Count Giovanni Volpi of Venice, Italy who owned and managed a racing team known as Scuderia Serenissima Republica di Venezia.

Scuderia Serenissima entered the Ferrari 250 TRI/61 at Sebring in 1962 with Brit Graham Hill and Swiss Jo Bonnier scheduled to drive. During race week Hill badly injured his back trying to carry some heavy spare parts for the car and he was replaced by a 23-year-old Belgian by the name of Lucien Bianchi, who was racing in America for the first time.

The Constructor’s Championship had three separate classes of GT cars, the smallest of which were cars under 1000cc. To accommodate the smaller cars a separate three-hour race was held the day before the 12 hours along with a 25-lap Formula Junior race. Both events were hotly contested, much to the delight of the race fans who had been camped out all week.

The preliminary three-hour race and Formula Junior races were not amateur events as many of the top drivers for the 12 hours were entered. In the three-hour race drivers like Stirling Moss, Innes Ireland, Steve McQueen and Pedro Rodríguez would drive factory Austin-Healey Sprites. Roger Penske, Bruce McLaren, Olivier Gendebien and Mauro Bianchi would drive Fiat-Abarth 1000s.

Unfortunately for the drivers and fans alike, the beautiful weather that had blessed the track all week gave way to a deluge of rain Thursday that continued into Friday prior to the start of the 3-Hour race at 10 a.m.

Right up until the final hour of the 3- hour race Moss was still in the lead and with 30 minutes to go had built up a 21- second lead. Not known for slowing down, Moss continued to push his Sprite to the limit and with 20 minutes left spun his car on the wet track, allowing Bruce McLaren to close the gap.

With five minutes left the Sprites of Moss, Rodríguez and McQueen tried to come in for just enough fuel to finish the race. This caused great confusion in the pits and before they got it sorted out the more fuel-efficient Fiat-Abarths of Bruce McLaren and Walt Hansgen went into the lead, never to relinquish it. For the win McLaren averaged 78.4mph and Fiat- Abarth would now lead in the under 1000cc class for the Constructor’s Championship.

Buy This Issue | Access the Digital Issue | Subscribe to Vintage Motorsport

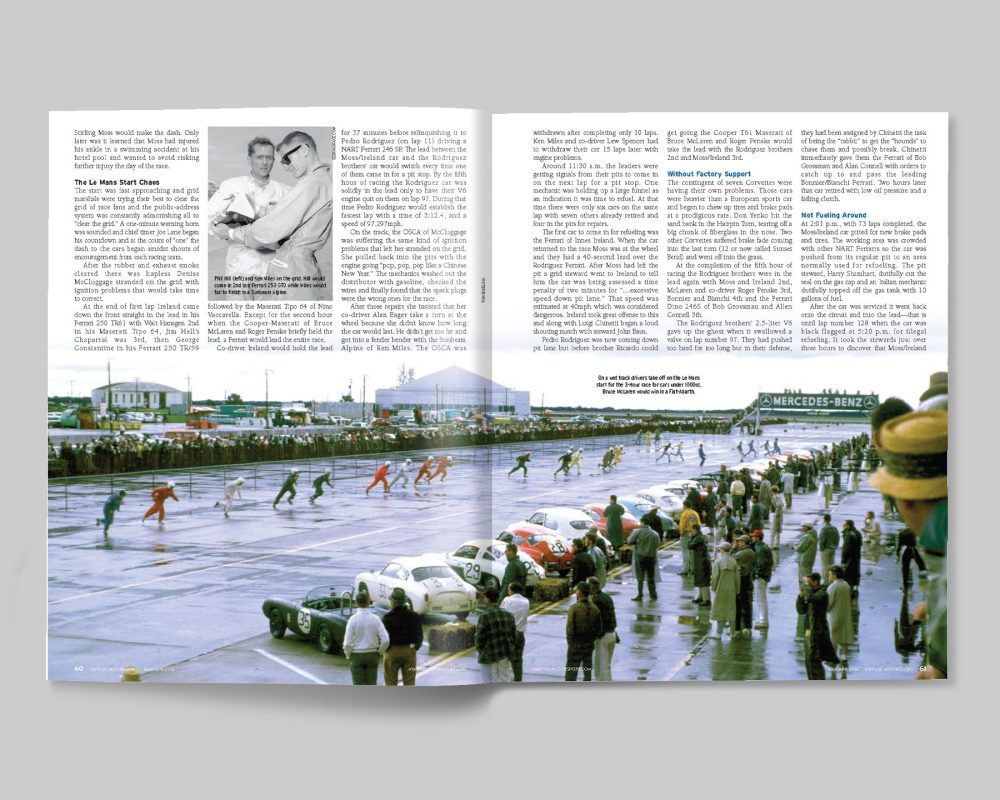

By race day (Saturday, March 24) the storm clouds had dissipated, and sunshine and partly cloudy skies greeted the arriving throngs of race fans trying to get into the track before the 10 a.m. start.

At 9:15 that morning all 65 cars that would start the race were on the grid with some still being worked on by mechanics. The drivers had congregated around Alec Ulmann for his traditional driver’s meeting speech, which he gave in several languages.

After the meeting drivers moved to their positions across the track and opposite their car for the Le Mans-style start. To the surprise of many Innes Ireland and not Stirling Moss would make the dash. Only later was it learned that Moss had injured his ankle in a swimming accident at his hotel pool and wanted to avoid risking further injury the day of the race.

The Le Mans Start ChaosThe start was fast approaching and grid marshals were trying their best to clear the grid of race fans and the public-address system was constantly admonishing all to “clear the grid.” A one-minute warning horn was sounded and chief timer Joe Lane began his countdown and at the count of “one” the dash to the cars began amidst shouts of encouragement from each racing team.

After the rubber and exhaust smoke cleared there was hapless Denise McCluggage stranded on the grid with ignition problems that would take time to correct.

At the end of first lap Ireland came down the front straight in the lead in his Ferrari 250 TR61 with Walt Hansgen 2nd in his Maserati Tipo 64, Jim Hall’s Chaparral was 3rd, then George Constantine in his Ferrari 250 TR/59 followed by the Maserati Tipo 64 of Nino Vaccarella. Except for the second hour when the Cooper-Maserati of Bruce McLaren and Roger Penske briefly held the lead, a Ferrari would lead the entire race.

Co-driver Ireland would hold the lead for 37 minutes before relinquishing it to Pedro Rodríguez (on lap 11) driving a NART Ferrari 246 SP. The lead between the Moss/Ireland car and the Rodríguez brothers’ car would switch every time one of them came in for a pit stop. By the fifth hour of racing the Rodríguez car was solidly in the lead only to have their V6 engine quit on them on lap 97. During that time Pedro Rodríguez would establish the fastest lap with a time of 3:12.4, and a speed of 97.297mph.

On the track, the OSCA of McCluggage was suffering the same kind of ignition problems that left her stranded on the grid. She pulled back into the pits with the engine going “pop, pop, pop like a Chinese New Year.” The mechanics washed out the distributor with gasoline, checked the wires and finally found that the spark plugs were the wrong ones for the race.

After those repairs she insisted that her co-driver Alan Eager take a turn at the wheel because she didn’t know how long the car would last. He didn’t get too far and got into a fender bender with the Sunbeam Alpine of Ken Miles. The OSCA was withdrawn after completing only 10 laps. Ken Miles and co-driver Lew Spencer had to withdraw their car 15 laps later with engine problems.

Around 11:30 a.m. the leaders were getting signals from their pits to come in on the next lap for a pit stop. One mechanic was holding up a large funnel as an indication it was time to refuel. At that time there were only six cars on the same lap with seven others already retired and four in the pits for repairs.

The first car to come in for refueling was the Ferrari of Innes Ireland. When the car returned to the race Moss was at the wheel and they had a 40-second lead over the Rodríguez Ferrari. After Moss had left the pit a grid steward went to Ireland to tell him the car was being assessed a time penalty of two minutes for “…excessive speed down pit lane.” That speed was estimated at 40mph which was considered dangerous. Ireland took great offense to this and along with Luigi Chinetti began a loud shouting match with steward John Baus.

Buy This Issue | Access the Digital Issue | Subscribe to Vintage Motorsport

Pedro Rodríguez was now coming down pit lane but before brother Ricardo could get going the Cooper T61 Maserati of Bruce McLaren and Roger Penske would take the lead with the Rodríguez brothers 2nd and Moss/Ireland 3rd.

Without Factory SupportThe contingent of seven Corvettes were having their own problems. Those cars were heavier than a European sports car and began to chew up tires and brake pads at a prodigious rate. Don Yenko hit the sand bank in the Hairpin Turn, tearing off a big chunk of fiberglass in the nose. Two other Corvettes suffered brake fade coming into the last turn (12 or now called Sunset Bend) and went off into the grass.

At the completion of the fifth hour of racing the Rodríguez brothers were in the lead again with Moss and Ireland 2nd, McLaren and co-driver Roger Penske 3rd, Bonnier and Bianchi 4th and the Ferrari Dino 246S of Bob Grossman and Allen Connell 5th.

The Rodríguez brothers’ 2.5-liter V6 gave up the ghost when it swallowed a valve on lap number 97. They had pushed too hard for too long but in their defense, they had been assigned by Chinetti the task of being the “rabbit” to get the “hounds” to chase them and possibly break. Chinetti immediately gave them the Ferrari of Bob Grossman and Alan Connell with orders to catch up to and pass the leading Bonnier/Bianchi Ferrari. Two hours later that car retired with low oil pressure and a failing clutch.

Not Fueling AroundAt 2:01 p.m., with 73 laps completed, the Moss/Ireland car pitted for new brake pads and tires. The working area was crowded with other NART Ferraris so the car was pushed from its regular pit to an area normally used for refueling. The pit steward, Harry Shamhart, dutifully cut the seal on the gas cap and an Italian mechanic dutifully topped off the gas tank with 10 gallons of fuel.

After the car was serviced it went back onto the circuit and into the lead—that is until lap number 128 when the car was black flagged at 5:20 p.m. for illegal refueling. It took the stewards just over three hours to discover that Moss/Ireland had violated a rule that a car cannot get refueled until they have completed at least 20 laps from the last refueling (paragraph 9.k of Official Racing Regulations). When Ireland came in for brake pads and tires his car had only covered 17 laps since the last pit stop and when the car was refueled it was in violation of the rules. Since NART had not assigned anyone to do lap charts for the car, then no one was available to prevent the refueling. At the time of the disqualification the Moss/Ireland car had a two-lap lead and was running beautifully.

To say that Moss and Ireland were not happy would be an understatement. Ireland’s language was more “colorful” as he let loose with some adjectives about the race stewards, their family history, the ARCF, and other race officials and his choice of words, as my mother would say, could make a sailor blush. Even Luigi Chinetti got into the fray by threatening to withdraw the entire list of NART entries if the Moss/Ireland car was disqualified.

While the Moss/Ireland drama with all its shouting and cursing was taking place, the Ferrari 250 TRI/61 of Bonnier and Bianchi were reaping the rewards of their pre-race strategy to take it easy, not push the car and maintain consistent lap times. All of this was a plan worked out and directed by team manager Nello Ugolini. In his words, “If the drivers can be made to go slow, we win.”

For the entire race, they were never lower than 6th position and during the first, third and fourth hours held a steady 4th overall. As the expected retirements began to mount they would get to 2nd place during the sixth and seventh hours. With the disqualification of the leading Moss/Ireland Ferrari they assumed the top spot by the end of the eighth hour and would hold on to that position for the rest of the race.

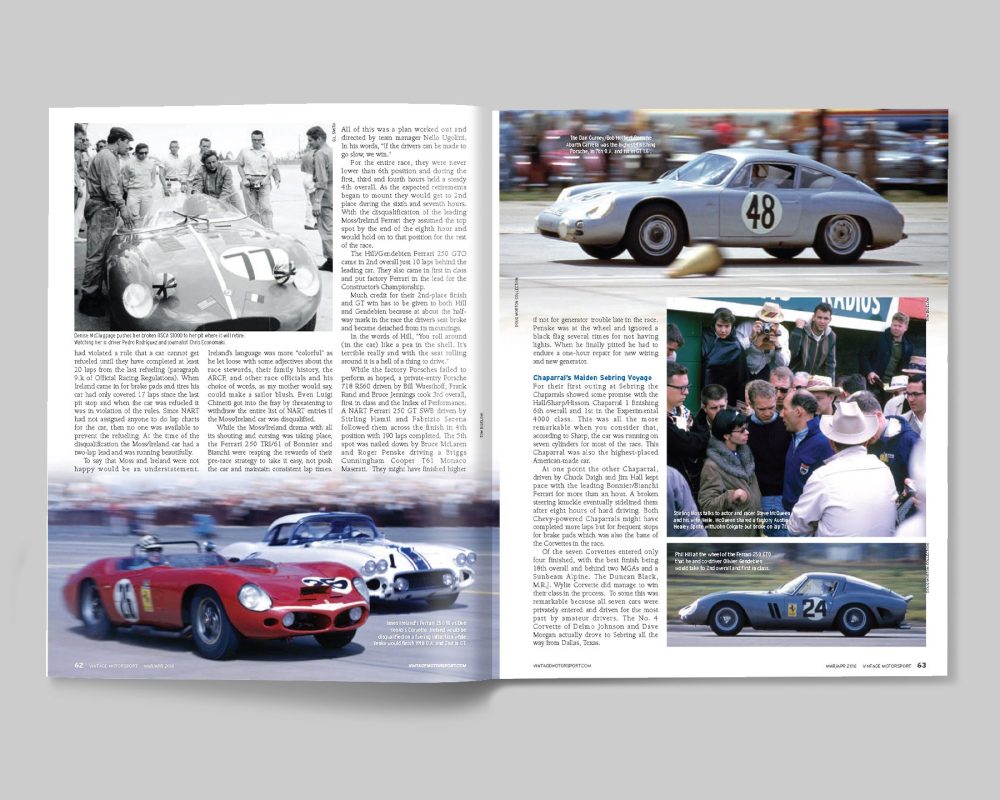

The Hill/Gendebien Ferrari 250 GTO came in 2nd overall just 10 laps behind the leading car. They also came in first in class and put factory Ferrari in the lead for the Constructor’s Championship.

Much credit for their 2nd-place finish and GT win has to be given to both Hill and Gendebien because at about the halfway mark in the race the driver’s seat broke and became detached from its mountings.

In the words of Hill, “You roll around (in the car) like a pea in the shell. It’s terrible really and with the seat rolling around it is a hell of a thing to drive.”

While the factory Porsches failed to perform as hoped, a private-entry Porsche 718 RS60 driven by Bill Wuesthoff, Frank Rand and Bruce Jennings took 3rd overall, first in class and the Index of Performance. A NART Ferrari 250 GT SWB driven by Stirling Hamil and Fabrizio Serena followed them across the finish in 4th position with 190 laps completed. The 5th spot was nailed down by Bruce McLaren and Roger Penske driving a Briggs Cunningham Cooper T61 Monaco Maserati. They might have finished higher if not for generator trouble late in the race. Penske was at the wheel and ignored a black flag several times for not having lights. When he finally pitted he had to endure a one-hour repair for new wiring and new generator.

Buy This Issue | Access the Digital Issue | Subscribe to Vintage Motorsport

Chaparral’s Maiden Sebring VoyageFor their first outing at Sebring the Chaparrals showed some promise with the Hall/Sharp/Hissom Chaparral 1 finishing 6th overall and 1st in the Experimental 4000 class. This was all the more remarkable when you consider that, according to Sharp, the car was running on seven cylinders for most of the race. This Chaparral was also the highest-placed American-made car.

At one point the other Chaparral, driven by Chuck Daigh and Jim Hall kept pace with the leading Bonnier/Bianchi Ferrari for more than an hour. A broken steering knuckle eventually sidelined them after eight hours of hard driving. Both Chevy-powered Chaparrals might have completed more laps but for frequent stops for brake pads which was also the bane of the Corvettes in the race.

Of the seven Corvettes entered only four finished, with the best finish being 18th overall and behind two MGAs and a Sunbeam Alpine. The Duncan Black, M.R.J. Wylie Corvette did manage to win their class in the process. To some this was remarkable because all seven cars were privately entered and driven for the most part by amateur drivers. The No. 4 Corvette of Delmo Johnson and Dave Morgan actually drove to Sebring all the way from Dallas, Texas.

With two hours left in the race the Bonnier/Bianchi Ferrari was holding onto what would be a 10-lap winning margin. About 40 minutes later the signal went out to Bianchi to come in for the final fuel stop and to hand over to Jo Bonnier who would take the checkered flag.

What Team Orders?Then something happened that added even more drama to an already drama-filled Sebring. Bianchi brought in the car but, as the mechanics worked on it, he refused to get out of the car and turn it over to Bonnier.

Several people went to him, asking him then ordering him to remove himself from the car. He refused and said very little. Then the shouting and cursing followed but Bianchi sat firmly in his seat gripping the steering wheel tightly. He was determined to get his first chance to take the checkered flag at a major international event. It was also the first American race for the young Bianchi and he wanted to make the most of it. The look on Jo Bonnier’s face was one of disgust and to avoid wasting any more time they let Bianchi take out the car for the win.

The distance covered by the winning Bonnier/Bianchi Ferrari was 1,071 miles (206 laps) which failed to break the record (1,092 miles) set by Hill and Gendebien in 1961. The same went for average speed with Bonnier/Bianchi doing 89.142mph compared to Hill and Gendebien who did 90.7mph in 1961. Pedro Rodríguez established a new record for the fastest lap with 97.264mph in his 2.5 liter Ferrari. Only 35 out of 65 starters were listed as still running at the end of the 12 hours.

The highest-placing British car, apart from the Cooper-Maserati, was the E-Type Jaguar driven by Briggs Cunningham and John Fitch, which came in 14th overall and 1st in class and ahead of the Corvettes. All three MGAs finished and they were applauded in the press following the race for their reliability, and the factory touted these results in magazine and newspaper advertisements for weeks to come. The Austin-Healey Sebring Sprite of Steve McQueen and John Colgate failed to finish when, according to the official notes of the pit steward, they struck a bird on the course on lap 71 and the strike damaged their radiator beyond repair.

The “brouhaha” over the disqualification of the Moss/Ireland Ferrari, when it was leading, did not end when the checkered flag dropped on the 1962 Sebring 12 Hour. For days and weeks following the event the motorsports press and motorsports pundits weighed in on the matter and eventually the international sanctioning body (FIA) took action by eliminating the 20-lap minimum before refueling. For 1963 there would be no restrictions on refueling stops.

Buy This Issue | Access the Digital Issue | Subscribe to Vintage Motorsport

With the overall win at Sebring in 1962, factory Ferrari held the Sebring record of five wins in 12 years with no other make winning more than once. They would repeat in 1963 with Ferraris in the top six spots and in 1964 they would hold the top three. Ferrari wouldn’t win the top spot again until the 1970 Sebring race, which many say was the best Sebring ever run.

[ad_2]

Source link